Shadowbox Construction (And Fiery Paint...)

My sculptures often involve flameworking, to shape and form glass, so I am used to the fact that there will be some fire involved at some point in the process. That’s all as it should be. However, I do not expect that my finished artwork will actually catch on fire. That’s a completely different story, so read on to hear the tale of the Fiery Paint.

It starts out with the seemingly simple idea of building a shadowbox to display my lighted glass stars. Filled with krypton gas that lights up in moving filaments of plasma, the stars are best viewed in a dark room- but the next best thing is to view them with a darkened space surrounding them. In many ways this is even a better option than an entirely dark room, because the darkness of the box enhances the lighted sculpture while giving it the flexibility of being displayed in a variety of differently lighted areas. In the previous post I began designing a shadowbox where the glass sculptures would be securely supported inside, and the glass would be protected, while at the same time being easily removable.

I decided to build the shadowbox out of wood since this is the easiest and most practical material to build what I had in mind. Also, since the stars are lit using a high-voltage, high frequency power supply (similar to those that power neon signs), I needed to use a material that is not electrically conductive. One of the typical guidelines for displaying plasma sculptures is that they should not be in easy reach of conductive surfaces like metal, because if someone were to touch the plasma sculpture while at the same time touching a nearby piece of metal they could get a minor electrical shock. Furthermore, the close proximity of metal can sometimes interfere with the appearance of the plasma effects. Sometimes a metal stand can be used if it is designed correctly, but as a general rule it’s best not to use metals. (For example, science museums that display plasma globes are advised to build a display base out of a non-conductive material such as wood or plastic to eliminate this issue, and it is much the same for the type of plasma sculptures that I am making.)

To begin making the box, I started with the four pieces of wood for the sides. I wanted these to have mitered corners—that is, corners that fit together at a 45-degree angle. This way there are no visible joins on the sides to be distracting, and it will look more smooth and seamless at the corners, much like a picture frame but deeper. The wood pieces also needed to be wide enough to create walls deep enough to contain the glass star plus a fixture that will attach the star to the back panel inside. The fixture, which I later made from PVC pipe parts, adds a bit of extra length to the star sculpture so that had to be taken into account.

Never having tried to glue angled corner joints before, I quickly realized that without the proper method of clamping, such an endeavor turns into a mess of dripping glue and corners that don’t line up properly as the glue is setting. So I made some corner braces out of rectangular scraps of wood, by cutting two holes out of each one. Gluing one corner of the box at a time, I clamped these braces into the corners while the glue was drying to make sure the corners lined up. A bit awkward (and I’ve since learned about a better method involving a nail gun) but it worked.

Because the pieces of wood I used turned out to be a little bit warped, a few of the corners ended up with gaps in them despite the careful clamping. But I found that it worked well to use some wood putty or “plastic wood” to fill in these gaps, which I then sanded smooth after it dried. After that you can’t tell that any gaps were there.

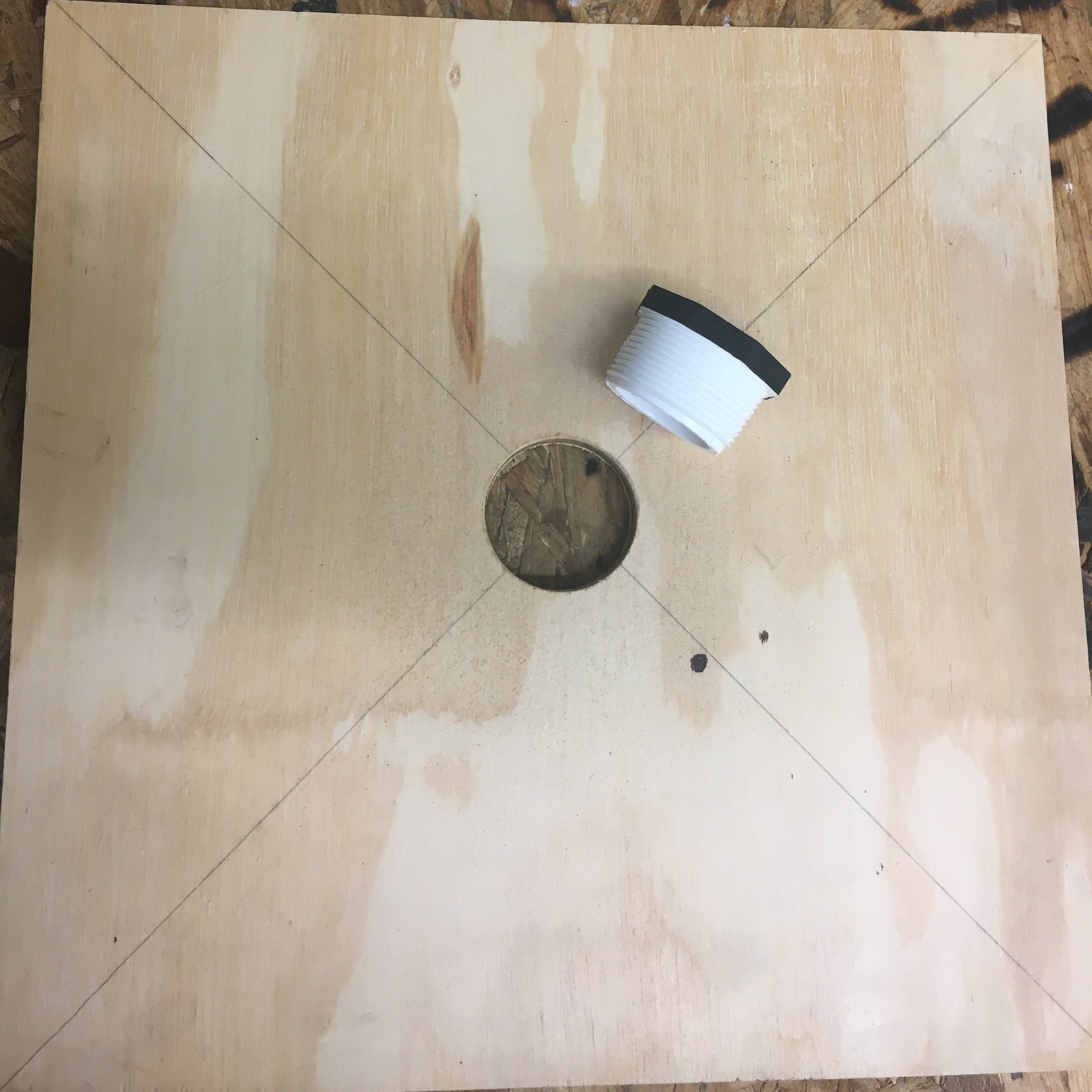

For the back panel, I cut a hole in the center using a hole saw. This is cut to match the size of a threaded PVC fitting that will go through from the back, to the inside of the box, and will be part of the support fixture for the star. I glued this in place with epoxy. As you’ll see later, the threaded part will attach to the star fixture, making it so the star can be screwed in to the fixture—much like a standard lightbulb.

After assembling the box, I painted it black inside and out— using a flat, matte black for the inside, to enhance the “total darkness” effect, and a semi-gloss type of black paint for the outside of the box. The star fixture will also be painted a matte black so that it “disappears” inside the dark space.

Next I made the rest of the fixture for the glass star, using an assembly of different types of PVC pipe fittings. Once I figured out which size fittings I needed, and how they would connect together, the whole process became easier, but it initially took a while to figure out the design. I documented the process of making it in the video below:

Now, if you watched until the end it probably looked like it should be all done now… but wait, there is a problem…

Thinking that it was all done (finally!) I switched on the power supply, but instead of the star lighting up the way it is supposed to, the electrical socket that I installed on the side of the star fixture immediately began sparking. At first I couldn’t figure out why. I checked the wire connections and everything seemed to be securely connected, nothing that would normally cause a problem. I even took the wiring apart and replaced the socket, thinking that maybe there was something wrong with that particular one (though I couldn’t imagine what could be wrong with it, it was brand new). But this didn’t solve the problem because I tried turning on the star again (just for a second, while keeping my hand on the switch ready to immediately turn it off) and again, the same problem occurred. The socket on the side of the star fixture sparked, and the base of the fixture, where it attaches to the back panel of the shadowbox, actually started to catch on fire! (Luckily no harm was done, to the shadowbox or to my room, I turned it off right away.) But spontaneous combustion is not an ideal feature for a wooden shadowbox to have...

So WHY was this happening? It turns out that the electrical wiring wasn’t the problem at all—the problem was the black paint. I would never have expected this, but it turns out that the kind of black paint I used is actually electrically conductive! I mentioned before that plasma sculptures should not be displayed close to metal surfaces; instead a display stand should be built out of non-conductive materials like wood or plastic. But even though I did build it out of wood and plastic, the paint I used effectively turned it into the equivalent of a metal-covered box. This means that the high voltage from the socket was arcing (jumping with a spark) to the very conductive painted surface right next to it. And the high voltage from the wiring inside the base of the star fixture—which was very close to the painted back panel—was also igniting the paint back there.

I did not happen to be documenting the sparks and fire to show what that looked like, and for the sake of safety I am not going to try to recreate it, but I will show you an experiment I did with a high-voltage test coil, to demonstrate that the paint I used is definitely electrically conductive. Until now, I didn’t know that paint could be electrically conductive so it’s not something I would ever have thought to check. Now I know better!

The reason that some black paint is electrically conductive is due to its ingredients, because sometimes graphite (a conductive material) is used to make the dark pigment. There may be other ingredients that cause this too. But it depends on the paint. So I took a sample of some other different kinds of black paint and tested them all, hoping to find one that is inert. The results were surprising (and also annoying). The good news is that there are plenty of other black paints I can use that will be fine— but most unluckily I just happened to choose one that was very electrically conductive.

To paint the inside of the box and the fixture, I had used a base coat of Black 2.0, with a top coat of Black 3.0. (The Black 3.0 is a very matte black that was recommended to me for this project, because it gives little to no reflection of light.) It turns out that Black 2.0 is conductive, while Black 3.0 (made by the same brand) isn’t. Who knew? So even though it was underneath the Black 3.0, it still caused a problem. On the outside of the box, I originally painted it the same as the inside, but then I decided to give it a more semi-gloss look and added another coat on top of that (this was a Satin Black interior/exterior paint by the brand Behr.) When I tested this paint, it was surprisingly not conductive at all. So even though the Black 2.0 was underneath two more layers of non-conductive paint here, it didn’t make any difference—it made everything conductive. *sigh*

So what to do? Sanding off multiple coats of black paint would be messy and difficult. And as I found out, simply painting over a conductive paint doesn’t help remove its electrical effects. It would be faster to re-make some parts. At the very least I knew I needed to re-make a new PVC fixture as well as the back panel, so I could paint these with a suitable alternative (I could use Black 3.0 on its own, or some of the other paints I tested.) With these replaced, the wiring will not be too close to anything electrically conductive that it would draw an arc. It might have been okay to leave the outside of the box painted with conductive paint, but I decided I would feel a lot better about displaying it if I can guarantee there is no possible reason for concern in the future! So the walls of the box were remade too—basically, everything except the glass star had to be remade. (But it went faster this time since I knew what I was doing, and this time I had some help with the wall construction thanks to Richard Burbidge, who also made the concrete base for my “Tethered to the Stars” sculpture.)

This time I ended up using a different kind of matte black paint called Musou for the inside of the new shadowbox and the fixture (I could have used plain Black 3.0 again, but I didn’t have enough left.) And the outside has a black wood stain instead of paint. And so in the end, I have a finished, new and improved shadowbox that I promise will not catch on fire.

See the finished effect here: